Any questions ?

Please email questions to shalom@tov/com

Notice: Test mode is enabled. While in test mode no live donations are processed.

Please email questions to shalom@tov/com

Notice: Test mode is enabled. While in test mode no live donations are processed.

The history of Israel unfolds as a tapestry of ancient origins, conquests, exiles, and resurgences, marked by profound religious significance, geopolitical struggles, and enduring conflicts. Like much of ancient history, reliable texts are absent and what is recounted as history is a repetition of ancient myths. The overriding certainty of the story is that of a land constantly in a state of conflict.

The first part of the story, lacking any historical evidence to the contrary is told through the eyes of the Hebrew Bible, the Tanakh. Before the story of David, it is mostly legends. From the time of David and Solomon there are plausible historical figures, although the scale is hotly debated. After the 9th century, highlighted in blue below, actual history in the modern sense starts to emerge.

The story begins in the Bronze Age, around 2000 BCE, when the region was inhabited by Canaanite peoples, a Semitic group with city-states like Jericho and Megiddo. According to Jewish tradition, the patriarch Abraham migrated from Mesopotamia to Canaan around 1900–1750 BCE, establishing a covenant with God that promised the land to his descendants. This period saw the emergence of the Israelites, descendants of Abraham’s grandson Jacob (renamed Israel), whose twelve sons formed the basis of the Twelve Tribes of Israel. By around 1400 BCE, the Hebrews, having endured slavery in Egypt, escaped under Moses’ leadership in the Exodus, wandering the Sinai for 40 years before entering Canaan circa 1300–1200 BCE. Archaeological evidence supports a gradual settlement of Israelite tribes in the highlands, blending with local Canaanites, though conflicts with Philistines along the coast persisted into the Iron Age.

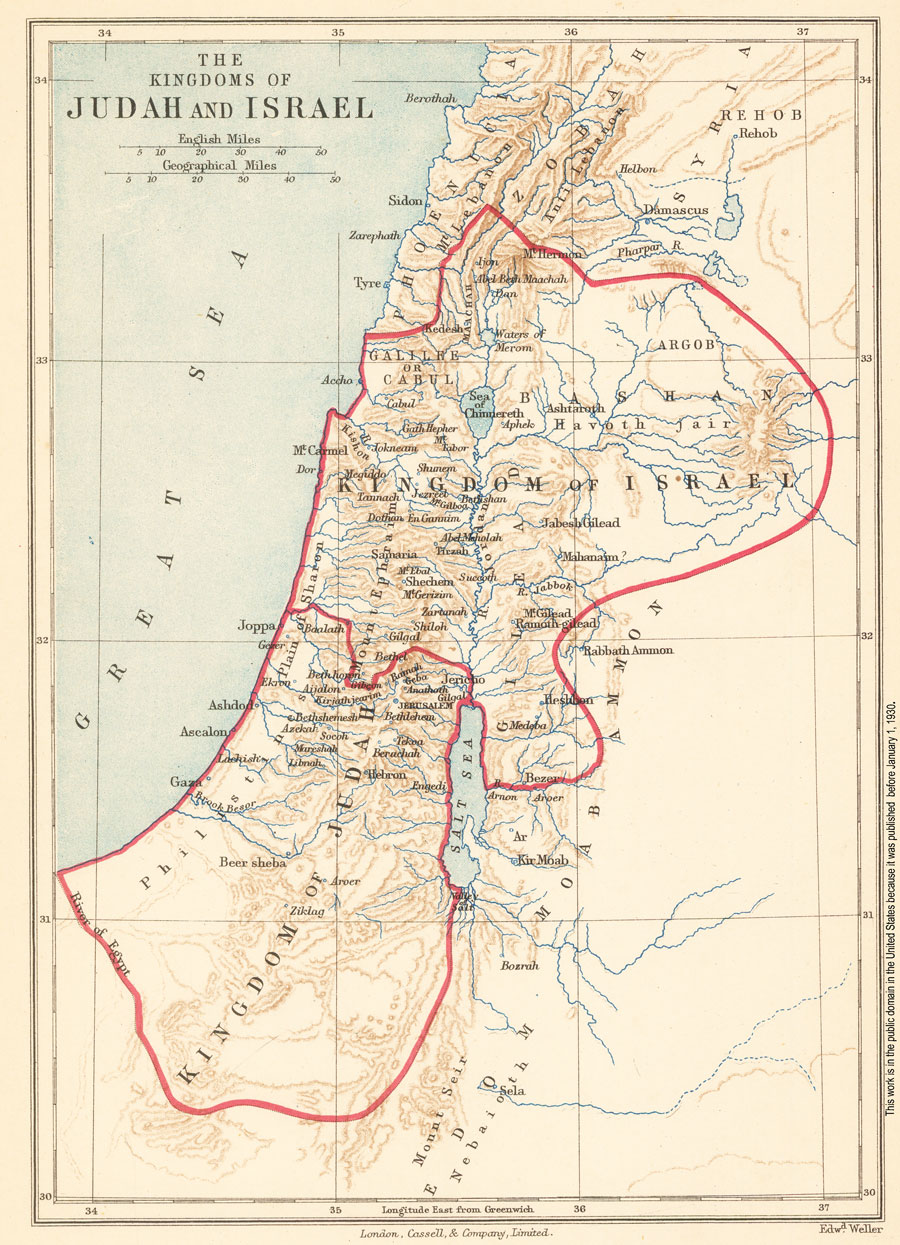

By around 1012 BCE, the tribes unified under King Saul to form the United Kingdom of Israel, a monarchy that reached its zenith under David (circa 1000–961 BCE) and Solomon (circa 961–931 BCE). David conquered Jerusalem, making it the capital, while Solomon built the First Temple around 962 BCE as a center of worship. After Solomon’s death in 931 BCE, the kingdom split: the northern Kingdom of Israel (ten tribes) with its capital at Samaria, and the southern Kingdom of Judah (two tribes) centered on Jerusalem. The north fell to the Assyrian Empire in 722 BCE, leading to the dispersal of its people (the “Lost Tribes”). Judah endured until the Babylonian conquest in 586 BCE, when King Nebuchadnezzar destroyed the Temple and exiled elites to Babylon.

The Babylonian Exile (586–539 BCE) marked a pivotal shift, as Jews maintained their identity through scripture and synagogue practices. Persian King Cyrus allowed their return in 539 BCE, leading to the rebuilding of the Second Temple by 515 BCE under Persian rule. Alexander the Great’s conquest in 332 BCE introduced Hellenistic influences, followed by Seleucid and Ptolemaic rule. A revolt by the Maccabees in 167–160 BCE established the Hasmonean dynasty, a brief period of Jewish independence. Roman intervention began in 63 BCE under Pompey, installing client kings like Herod the Great (37–4 BCE), who expanded the Temple. Tensions erupted in the Great Revolt (66–73 CE), culminating in the destruction of the Second Temple in 70 CE by Titus. The Bar Kokhba Revolt (132–135 CE) against Emperor Hadrian resulted in massive casualties and the renaming of Judea to “Syria Palaestina” to erase Jewish ties.

The Hebrew language was largely erased from the remnants of the Jews during this period coinciding with the destruction of the second temple.

The Roman suppression accelerated the Jewish Diaspora, scattering communities across the Mediterranean, Europe, and beyond, though a remnant persisted in the land. Byzantine Christian rule (330–636 CE) marginalized Jews further. The Arab-Muslim conquest in 636 CE under Caliph Umar brought Islamic governance, with Jews and Christians as dhimmis (protected but subordinate). The Umayyad (661–750 CE) and Abbasid (750–1258 CE) caliphates saw periods of tolerance, including the construction of the Dome of the Rock in 691 CE. Crusader invasions (1099–1291 CE) briefly established Christian kingdoms, marked by massacres of Jews and Muslims. Mamluk rule (1250–1517 CE) followed, maintaining Islamic dominance.

Under Ottoman rule from 1517, the region known as Palestine was part of the empire’s Syrian provinces. Jews faced restrictions but maintained communities in Jerusalem, Safed, and Hebron. The 19th century brought reforms and European influence, amid rising Arab nationalism and Jewish immigration spurred by pogroms in Europe.

The word pogrom derives from the Russian verb gromít’ (громи́ть) meaning to sack, loot, or crush (an enemy). It first came into English around 1882 as meaning a violent riot aimed at expelling an ethnic group, particularly Jews.

Modern Zionism emerged in the late 1800s as a response to antisemitism, formalized by Theodor Herzl’s First Zionist Congress in 1897. Waves of Jewish immigration (Aliyah the “going up”) established agricultural settlements in their return to Zion. Jews migrating back to their ancestral homeland legally purchased land in from the Arab owners. The Jewish National Fund was established in 1901 to help Jews purchase land and migrate back to their homeland in Israel.

The Balfour Declaration of 1917 pledged British support for a “Jewish national home” in Palestine after Ottoman defeat in World War I.

Concurrent with the Zionist movement, the Hebrew language saw a revival, helping to bind the people together as a distinct ethic group as they migrated back to Israel.

Israel declared independence on May 14, 1948, triggering the Arab-Israeli War (1948–1949), where invading armies from Egypt, Jordan, Syria, Iraq, and Lebanon were repelled. The war resulted in Israel’s control of 78% of Mandate Palestine, Jordan annexing the West Bank and East Jerusalem, and Egypt occupying Gaza. Some 700,000 Palestinians fled or were expelled (the Nakba), while 800,000 Jews were displaced from Arab countries.The Suez Crisis (1956) saw Israel, Britain, and France attack Egypt over the canal nationalization. The Six-Day War (1967) preempted Arab mobilization, with Israel capturing the West Bank, Gaza, Sinai, and Golan Heights.

The Yom Kippur War (1973) involved surprise attacks by Egypt and Syria, leading to heavy losses but eventual ceasefires. Peace treaties followed: with Egypt (1979, returning Sinai) and Jordan (1994). The First Intifada (1987–1993) erupted on December 9, 1987, after an Israeli truck killed four Palestinians in Gaza’s Jabalia camp, sparking widespread protests, stone-throwing, and boycotts. Specific attacks included the stabbing of a Jewish merchant in Gaza on December 7, 1987, and intra-Palestinian violence against alleged collaborators, with over 1,000 Palestinians killed by fellow Palestinians. Israeli forces responded with live fire, killing around 1,100 Palestinians. The Oslo Accords (1993–1995) created the Palestinian Authority (PA) for limited self-rule.

The Second Intifada (2000–2005), or Al-Aqsa Intifada, began September 28, 2000, after Ariel Sharon’s Temple Mount visit, escalating into armed clashes and suicide bombings. Notable attacks included the October 12, 2000, lynching of two Israeli reservists in Ramallah by a Palestinian mob; the June 1, 2001, Dolphinarium disco bombing in Tel Aviv (21 killed); the March 27, 2002, Passover Seder bombing in Netanya (30 killed); and numerous bus bombings, like the August 19, 2003, Jerusalem bus attack (23 killed). Over 1,000 Israelis and 4,900 Palestinians died.

Groups like Hamas (founded 1987) and Hezbollah (1982) embody radical Islamist ideologies seeking Israel’s elimination, viewing it as an illegitimate “Zionist entity” on Islamic land (waqf). Hamas’s 1988 charter calls for jihad to liberate Palestine, drawing on Muslim Brotherhood roots. Hezbollah, backed by Iran, aims for Israel’s destruction through “resistance.” These ideologies justify violence, including intifadas, as defensive jihad against occupation. Extremists cite Quranic verses selectively: Quran 5:51 (“O you who believe! Do not take the Jews and the Christians as allies”), interpreted as prohibiting coexistence; Quran 5:82 (“You will surely find the most intense of the people in animosity toward the believers [to be] the Jews”); and Quran 9:29 (“Fight those who do not believe in Allah… until they give the jizyah willingly while they are humbled”), twisted to mandate subjugation or elimination of Jews in Israel. Such interpretations, promoted by figures like Hamas leaders and IUMS fatwas, fuel calls for armed jihad.

Palestinians have rejected multiple two-state offers, including the 1947 UN plan (seen as favoring Jewish immigrants over Arab majority), 1967 post-war proposals, Camp David (2000, rejected over Jerusalem, refugees, and borders), and Olmert’s 2008 offer (deemed insufficient for sovereignty and refugee rights). Reasons include perceptions of unequal land division, Israeli settlements fragmenting territory, lack of control over resources/water/borders, unresolved refugee returns (right of return for 1948 displacees), and East Jerusalem as capital. From a Palestinian perspective, offers perpetuate occupation; critics argue rejectionism stems from leaders prioritizing total liberation over compromise.

Israel’s population within its pre-1967 borders is approximately 10.1 million: about 76.6% Israeli Jews (7.732 million), 20.9% Arab Israelis (2.114 million, mostly Muslim with Christian and Druze minorities), and 2.5% others (non-Arab Christians, etc.). The West Bank has around 3 million Palestinians (Arabs, ~98%) and 503,000–700,000 Israeli Jews in settlements (~14–20% of WB total). Gaza’s ~2.2 million are nearly 100% Palestinian Arabs (Muslim majority). Overall, including territories, Jews comprise ~51–55%, Arabs ~45–48%, with small other groups. Arab Israelis enjoy citizenship but face socioeconomic disparities.

The name West Bank is a modern term comprising the land know in Biblical times as Judea and Samaria. Prominent ancient cities in the Judea and Samaria are Jeruslaem, Bethelem, Hebron, Jerico, and others associated since ancient times with the Biblical decedents of Abraham, Isaac, and Jacob.

Both Muslims and Jews trace their ancestry to these Biblical characters. Jews say Israel is their Promised Land because God gave it to them, and Muslims say they have the same promise. Muslims claim a superior and superseding right because Al-Ma`idah 5:21 says “O my people, enter the Holy Land which Allah has assigned to you and do not turn back [from fighting in Allah ‘s cause] and [thus] become losers.”

The late Muslim scholar, Sheikh `Atiyyah Saqr, former Head of Al-Azhar Fatwa Committee, states: “Though, seizing the chance of Muslims’ lapsing in weakness and deviating from Allah’s teachings, the Jews have occupied Palestine, they will never remain there forever, for the evil within themselves is beyond description. They will suffer another defeat and severe blow; we hope this will be at the hands of Muslims once they return back to their Lord and be unified again.”

Maximilian Carl Emil Weber

The lessons for thoughtful world leaders to assess present-day reality are found in the writings of Max Weber’s Economy and Society: An Outline of Interpretive Sociology published posthumously in English in 1968, 48 years after his death in 1920.

Central to Weber’s analysis is his dissection of the modern state, which he defines as “a state is a human community that (successfully) claims the monopoly of the legitimate use of physical force within a given territory.” This definition encapsulates the state’s unparalleled power to define and enforce what constitutes law, positioning legality not as an abstract moral ideal but as a product of coercive domination backed by the threat of violence. Law, in Weber’s sociology, emerges from this monopoly: legal norms are those upheld through the state’s physical coercion, creating a system where compliance is induced by the expectation of official action. While this may sound abrasive to some, it is central to the existence of all states, even the United States. The U.S. was born in revolution (war) and enshrined a Constitution and form of government that has endured giving individual freedom to the greatest number of people in history. It’s laws are enforced, by violence if necessary when voluntary compliance fails.

Modern sovereignty law, particularly post-1945 international law, is structured around different assumptions. While Weber explores how authority is constituted and maintained internally, contemporary legal doctrine focuses on how states are recognized, constrained, and regulated externally. The two frameworks intersect in conceptual points but differ radically in normative purpose, legal structure, and implications for territorial conflict.

After the devastation of the Second World War, the international community undertook a radical redefinition of sovereignty to prevent a return to the global politics of annexation.

Article 2(4) of the UN Charter prohibits:

and does not recognize conquest as a path to sovereignty. The only accepted uses of force are:

Even successful conquest does not create legitimate sovereignty. This is the opposite of Weber’s “successful claim” criterion.

Since 1945, international law has prohibited the acquisition of territory by force, even in defensive wars. On paper, this norm is universal. In practice, however, states and the United Nations apply it unevenly. Israel is repeatedly and emphatically condemned, especially regarding East Jerusalem and the Golan Heights, while other states’ annexations or occupations (Tibet, Northern Cyprus, Crimea, Western Sahara, South China Sea islands, etc.) are met with much weaker condemnation, selective enforcement, or long-term normalization. The result is a pattern of normative hypocrisy rooted not in a legal double standard within doctrine but in the political structure of the UN system and the geopolitical interests of member states.

Unlike most territorial disputes, the Israel–Palestine question was placed under direct UN authority through the 1947 Partition Plan, multiple Security Council resolutions, UNRWA, and ongoing General Assembly involvement. Because the UN considers itself historically involved, the conflict receives continuous diplomatic attention and moral scrutiny.

By contrast, Tibetan independence, Moroccan Western Sahara control, or Turkish presence in Cyprus are treated as regional or internal matters, not as issues created by the UN. The level of international engagement is therefore vastly different.

In the General Assembly:

22 Arab League states

56 OIC states

120 Non-Aligned Movement states

form a large, consistent voting bloc. These states reliably pass resolutions on Israel, often by margins such as 150–10 or 120–8. No comparable bloc exists to champion Tibet, Kurds, Western Sahara, or Crimean Tatars.

Thus, condemnation reflects bloc politics, not impartial legal consistency.

Some annexing states are simply too powerful or strategically important to confront:

China in Tibet and the South China Sea

Turkey in Northern Cyprus

Russia in Crimea

Morocco in Western Sahara

Challenging these actors would require diplomatic confrontation with major military or economic powers. Many states prefer silence or symbolic statements rather than meaningful pressure.

Israel lacks equivalent systemic protection. The United States occasionally shields Israel in the Security Council through the veto, but not in the General Assembly, where condemnations are automatic and overwhelming.

Israel argues that its post-1967 territories were acquired in defensive war, a category that historically (before 1945) sometimes allowed territorial adjustment. Modern international law rejects that view: self-defense permits repelling attack but not keeping territory captured, even if the other side initiated the conflict.

However, for other states, the UN either avoids serious action or accepts long-term consolidation. China, Russia, Morocco, and India justify territorial control through:

historical narratives

claims of internal security

demographic integration

political facts on the ground

The UN may object rhetorically but does not mobilize sustained, effective pressure.

Because Jerusalem and the conflict touch on Islam, Judaism, Christianity, colonial legacies, Western guilt, Arab nationalism, and global identity politics, Israel is subject to attention far beyond its strategic weight. Few territorial issues evoke comparable emotional or ideological resonance.

Israel’s annexation-related condemnations are not simply about the legal norm itself. They reflect a combination of UN structural politics, bloc dynamics, historical involvement, symbolic resonance, and geopolitical asymmetry. Other annexations are tolerated, ignored, or normalized because the UN lacks either the political will or the geopolitical capacity to consistently enforce the very norms it proclaims—thus revealing the normative hypocrisy of the post-1945 international order.

We welcome thoughtful essays or comments, possibly for publication on this site.