Any questions ?

Please email questions to shalom@tov/com

Notice: Test mode is enabled. While in test mode no live donations are processed.

Please email questions to shalom@tov/com

Notice: Test mode is enabled. While in test mode no live donations are processed.

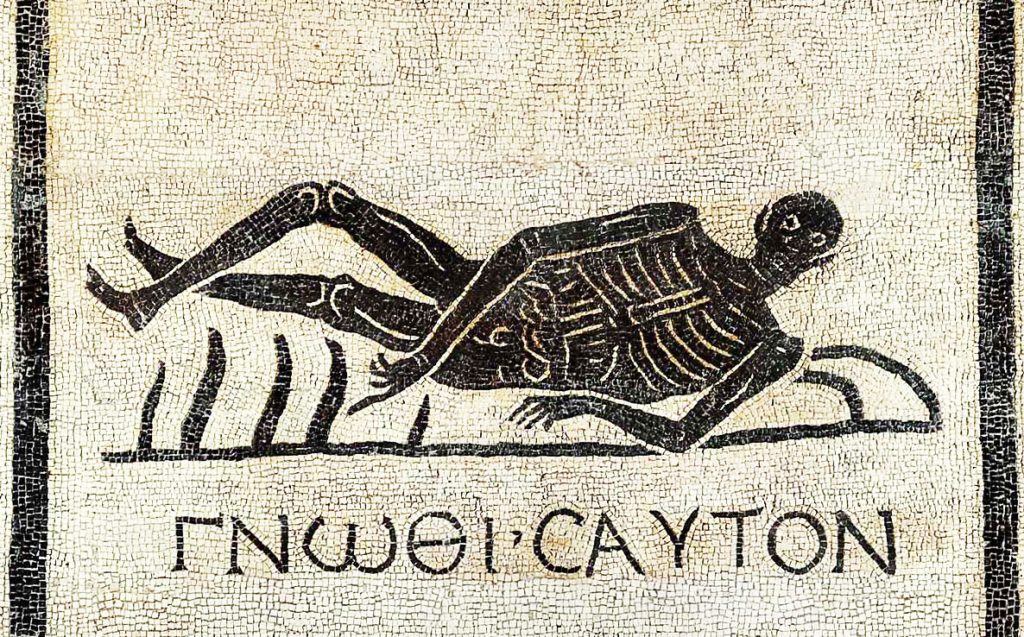

Few ideas have traveled as far, or changed as profoundly, as the ancient Greek injunction “Know Thyself.” Born as a religious maxim at Delphi, the phrase becomes the core of Socratic ethics, the foundation of Platonic metaphysics, the organizing principle of Stoic philosophy, a theological beacon for Augustine, the ground of certainty for Descartes, and eventually the battleground for modern psychology and neuroscience. This chapter traces the transformation of self-knowledge from antiquity to the contemporary age, showing how each era reinterprets the meaning, method, and purpose of knowing oneself.

The original inscription of "Know Thyself" (Γνῶθι σεαυτόν) at the Temple of Apollo in Delphi does not still exist today, as the temple was destroyed and rebuilt multiple times over centuries, with no surviving physical artifacts of that specific maxim. The phrase is known primarily from ancient literary sources, such as Plato and Pliny the Elder, who described it as one of the Delphic maxims inscribed in gold letters at the temple entrance by at least the 5th century BC.

The earliest form of “Know Thyself” appeared on the forecourt of the Temple of Apollo at Delphi, engraved alongside other maxims urging moderation and self-restraint. In this archaic context, self-knowledge functioned as a moral warning: humans must recognize their limits, avoid hubris, and understand their place beneath the gods. The maxim did not call for philosophical introspection but for awareness of one’s finitude and the dangers of overstepping the human condition. Its purpose was civic and religious, reminding mortals that self-delusion invites ruin and that wisdom begins with humility before the divine order.1

Socrates revolutionizes the Delphic command by transforming it into a philosophical method and ethical demand. For him, self-knowledge begins with acknowledging one’s own ignorance, a paradoxical form of wisdom that fuels continuous questioning. In the dialogues of Plato and Xenophon, Socrates relentlessly examines the beliefs of others, showing that most people hold contradictory or ungrounded views about justice, courage, temperance, and piety. Through the elenchus, he reveals that true self-knowledge requires examination of one’s assumptions, exposure of error, and pursuit of virtue. As he declares in Plato’s Apology, “the unexamined life is not worth living.”2 Self-knowledge is thus the ethical core of philosophy: a lifelong commitment to scrutiny, improvement, and care of the soul.

Plato inherits Socrates’ emphasis on self-examination but expands it into a metaphysical and psychological doctrine. For Plato, the true self is the soul, structured into reason, spirit, and appetite. Self-knowledge requires recognizing which part should rule, reason, and allowing it to bring order to the whole. In the Republic, he equates self-knowledge with the discovery of the soul’s kinship with the Forms, especially the Form of the Good, the ultimate source of truth.3 The allegory of the cave dramatizes the soul’s ascent from illusion to knowledge, showing that self-knowledge is inseparable from understanding ultimate reality. To know oneself is to grasp one’s nature as a rational being capable of participating in the eternal.

Although both Xenophon and Plato were students of Socrates, their portrayals of “Know Thyself” differ sharply, revealing two distinct philosophical traditions. Xenophon’s Socrates, particularly in the Memorabilia, treats self-knowledge as a practical art: knowing one’s strengths, weaknesses, and capacities.4 For him, self-knowledge enables effective leadership, responsible action, and intelligent management of one’s affairs. It is the foundation of prudence and moral discipline. Xenophon’s Socrates remains a teacher of worldly wisdom, emphasizing self-command and realistic self-assessment.

Plato’s Socrates, by contrast, interprets self-knowledge as a gateway to the structure of the soul and its alignment with the Good. Where Xenophon emphasizes functional capability, Plato emphasizes the metaphysical orientation of the rational soul and its relation to truth. For Plato, self-knowledge demands an inward ascent beyond practical judgment toward philosophical illumination. The distinction is not one of contradiction but of depth: Xenophon offers the Socrates of civic virtue and personal discipline; Plato offers the Socrates of metaphysical inquiry and spiritual transformation.

The Stoic tradition carries Socratic ethics into a new cosmological register. For Epictetus, Seneca, and Marcus Aurelius, the essence of self-knowledge is the distinction between what lies within our control, judgments, desires, intentions, and what lies outside it, wealth, reputation, bodily health, and external events. The true self is the rational faculty, a fragment of the divine Logos.5 Self-knowledge means understanding one’s role in the natural order, accepting fate with equanimity, and cultivating virtue as the sole good. The Stoic sage knows himself by disciplining his inner life, not by altering the external world.

Augustine reinterprets the classical inward turn through the lens of Christian theology. In the Confessions, he examines memory, desire, and will as windows into the soul’s complex interiority.6 For Augustine, self-knowledge reveals both the soul’s restlessness and its dependence on God, who is “more inward than my inmost self.” Sin distorts human perception, making the heart opaque even to itself. Thus, true self-knowledge requires divine illumination, without which introspection remains shallow or misleading. Augustine transforms “Know Thyself” into a theological journey: to know oneself is to encounter one’s origin and destiny in God.

Descartes shifts the meaning of self-knowledge from moral or spiritual inquiry to epistemic foundation. Through methodic doubt, he eliminates all beliefs that could be questioned, discovering that only the act of thinking itself remains indubitable.7 “Cogito, ergo sum” becomes the anchor of certainty, and the self emerges as a thinking substance distinct from the body. Self-knowledge is no longer care of the soul or encounter with the divine but immediate awareness of consciousness, the foundation upon which science and philosophy must be built. Descartes transforms self-knowledge into the epistemological bedrock of modernity.

Kant reframes self-knowledge by arguing that the noumenal self, the “self-in-itself,” is unknowable; we can know only the phenomenal self, structured by the mind’s categories.8 Theoretical self-knowledge is thus limited. However, Kant insists that in the moral domain we know ourselves as free, rational agents bound by duty. Self-knowledge emerges not through introspection but through awareness of the moral law. To know oneself is to understand one’s autonomy and moral vocation, as well as the cognitive limits inherent to being human.

Nietzsche rejects the idea of a stable, discoverable self. Instead, he claims that the self is a dynamic multiplicity of drives and impulses, often obscured by moral and religious fictions.9 Self-knowledge means unmasking illusions, confronting the will to power beneath conscious thought, and overcoming inherited values. For Nietzsche, introspection often deceives; consciousness is merely a superficial narrative. True self-knowledge demands self-overcoming and creative self-fashioning. “Know Thyself” becomes an existential challenge of liberation rather than discovery.

Freud brings a scientific revolution to self-knowledge by asserting that the most significant mental processes occur in the unconscious, inaccessible to introspection.10 Dreams, slips of the tongue, and neurotic symptoms reveal repressed desires that shape behavior. Self-knowledge therefore requires analytic interpretation, not mere reflection. The ego is shaped, and often deceived, by the id and superego. Freud transforms “Know Thyself” into a clinical procedure: uncovering conflicts, interpreting symbols, and integrating repressed material.

Jung extends Freudian theory by introducing the collective unconscious and archetypes. For Jung, the task of self-knowledge is individuation, a lifelong process of integrating the shadow, anima or animus, and other unconscious elements into a balanced personality.11 Self-knowledge is symbolic, psychological, and spiritual: one must confront the mythic patterns underlying personal experience. To know oneself is to seek wholeness, not simply to expose repressed desires.

Existentialists like Jean-Paul Sartre and Martin Heidegger reinterpret self-knowledge as confrontation with freedom, contingency, and death. Sartre argues that humans lack a fixed essence and must create themselves through choices; self-knowledge means overcoming “bad faith” and accepting the burden of freedom. Heidegger, meanwhile, describes self-knowledge as understanding one’s being-in-the-world, defined by temporality, relationality, and finitude.12 Authenticity arises from facing one’s mortality and resisting societal conformity. For existentialists, self-knowledge is existential clarity, not introspective certainty.

Behaviorists like B.F. Skinner deny the validity of introspection altogether. The “self” is not an inner entity but a pattern of behaviors shaped by environmental reinforcements.13 Self-knowledge means understanding the contingencies that produce behavior, not accessing inner states. Freedom and self-awareness are reinterpreted as illusions masking causal relationships. Behaviorism shifts the meaning of “Know Thyself” from inner examination to empirical analysis of observable actions.

Humanistic psychologists such as Carl Rogers and Abraham Maslow restore inwardness by emphasizing authenticity, growth, and self-actualization. Rogers describes self-knowledge as closing the gap between the actual self and ideal self, achievable in relationships grounded in empathy and unconditional acceptance. Maslow presents self-knowledge as the realization of one’s potential, the apex of the hierarchy of needs.14 In this tradition, “Know Thyself” becomes a journey of discovery, integration, and psychological flourishing.

Post-structuralists like Michel Foucault and Jacques Lacan challenge the notion of a natural or stable self. Foucault argues that the self is produced by discourse and power, and self-knowledge requires understanding the historical forces shaping subjectivity.15 Lacan reinterprets Freud by claiming that the unconscious is structured like a language and that the self is inherently alienated within symbolic systems. Self-knowledge becomes critical insight into the mechanisms that construct identity, rather than revelation of an inner essence.

Contemporary neuroscience reframes self-knowledge as understanding the biological mechanisms that give rise to consciousness. Antonio Damasio describes multiple levels of self, proto-self, core self, autobiographical self, arising from bodily regulation and neural processes. Daniel Dennett argues that the self is a narrative construct, a “center of gravity” created by the brain.16 Self-knowledge thus involves recognizing the constructed and dynamic nature of identity and the limits of introspection.

Behavioral economists such as Daniel Kahneman and Amos Tversky reveal that the human mind is systematically irrational. Self-knowledge requires understanding one’s own heuristics and biases, including anchoring, availability, overconfidence, and confirmation bias.17 The mind’s intuitive processes often mislead, creating illusions of coherence and certainty. To know oneself is to recognize the architecture of error within the very mechanisms of thought.

Modern thinkers like Thomas Metzinger argue that the self is not a thing but a transparent self-model generated by the brain. One cannot know the self because there is no inner entity to be known, only processes creating the experience of selfhood. David Chalmers pushes the problem further, highlighting the “hard problem” of consciousness, how subjective experience arises at all.18 In this contemporary landscape, “Know Thyself” becomes an inquiry into the biological, computational, and phenomenological conditions that make experience, and the illusion of a self, possible.

From antiquity to neuroscience, “Know Thyself” evolves from a religious warning to a philosophical command, from a moral imperative to an epistemological foundation, from psychological exploration to an investigation into the nature of consciousness. Each era transforms its meaning, yet the maxim persists because it poses a question both universal and endlessly revisable: What kind of being am I, and how can I understand myself?

We welcome thoughtful essays or comments, possibly for publication on this site.